Last Updated on February 26, 2024

The COVID-19 pandemic has been such a challenging moment in history for many reasons. Yet even in the midst of quarantine and lockdown measures, forward-thinking professionals worked hard to solve problems and optimize patient care.

Even now, as the Western world attempts to return to pre-COVID normalcy, scientists, healthcare professionals, and designers are studying the pandemic and preparing for the future.

Today’s guest is a designer who was directly involved in efforts to design a new type of ventilator that could have alleviated widespread shortages.

We hope that looking at efforts like this helps to express the value that innovative design offers to the world at large.

Designer Jayati Sinha

Jayati Sinha is an in-demand physical and digital experience designer who has worked for many years on projects meant to benefit the common good and those in need.

Sinha is currently working with Fjord, a high-caliber design and innovation firm that’s part of Accenture Interactive. She formerly worked extensively with Fuseproject as part of the Environmental Design team, while also contributing to the industrial design, experience design, and strategy teams.

Fuseproject is a design and innovation firm led by influential designer, entrepreneur, and educator Yves Béhar.

During the height of the COVID-19 worldwide crisis, Sinha and fuseproject were asked to participate in the CoVent-19 Challenge.

Sinha sat down with us to talk about her participation in the CoVent-19 Challenge and the potential long-term benefits of being a part of this rigorous design event.

The CoVent-19 Challenge

As COVID-19 cases started to spike all around the globe, it became clear that ventilators would be crucial to keeping the most impacted patients alive.

Because difficulty breathing was the most dangerous effect of the virus on vulnerable persons, ventilators were used to pump oxygen into the airways of struggling patients.

However, many hospitals did not have adequate supplies of ventilators, which are themselves expensive and difficult to produce.

As a way of addressing this widespread shortage and potentially preparing for future scenarios as well, the CoVent-19 Challenge was created.

Sinha explains the premise of the challenge:

“The CoVent-19 Challenge was the creation of thirteen resident physicians, advisors, and several sponsoring organizations. The challenge was to develop a rapidly deployable mechanical ventilator in four weeks, for treating COVID-19 patients.”

This was a practical design challenge meant to source potential solutions for the ventilator shortage, centered on a new design that would be easier (and faster) to manufacture.

This event highlighted how design can be a powerful tool for solving problems, though the short timeline also presented participating designers with major challenges.

Design challenges

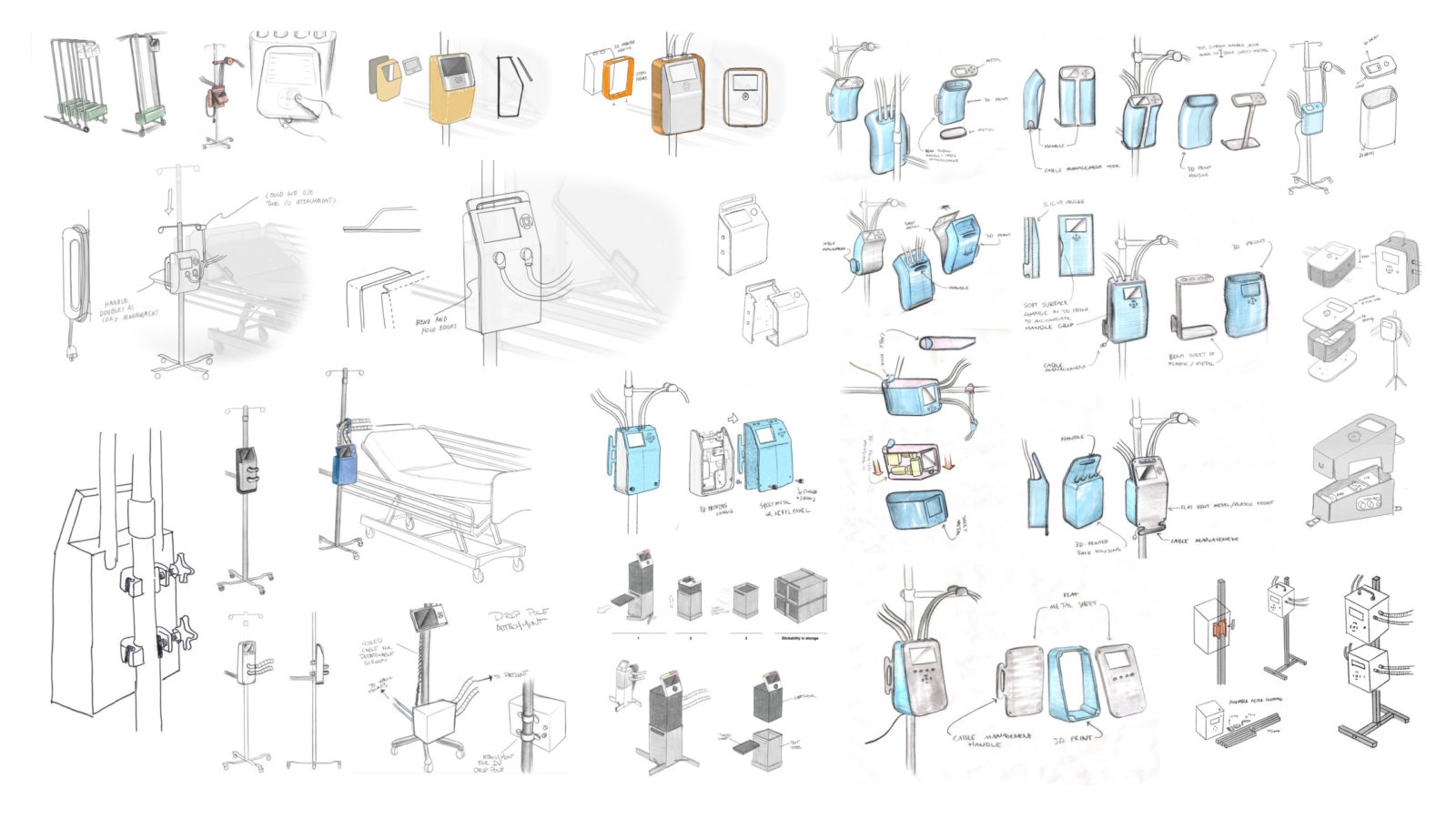

For Sinha and the team, many of the challenges encountered during this project were centered on (quickly) building a thorough understanding of how ventilators function and the requirements of a ventilator meant specifically for COVID-19 patients.

For obvious reasons, function was the priority for this design, and as Sinha explained to us, even relatively simple medical devices typically take between two to five years to progress through all stages of development, manufacturing, and official approval.

Condensing that timeline to an extreme degree only amplified the stresses of creating a high-quality design.

“Designing and engineering a ventilator in two and a half weeks was extremely stressful and seemed impossible when we started out, but we had a great team of designers from fuseproject, engineering experts from CIONIC, and two volunteer engineers from Accenture. So it was very challenging to figure out what the right questions would be to give us something to go on about a machine we were still learning about.”

The difficulty of conducting necessary research was exacerbated by pandemic conditions.

In particular, the team wanted to consult with respiratory therapists, doctors, and nurses, but for obvious reasons, these professionals were already incredibly busy attending to patients.

New ways of doing

If necessity is the mother of invention, then quarantine conditions and the strict timeline of this project actually benefited Sinha’s team.

The team had to find ways of doing everything more quickly and without the luxury of working at the same physical site.

These limitations had a serious impact on collaboration, communication, and the development process itself.

Under normal circumstances, everyone on the design team would be in the same place, and the development process would follow what’s called a waterfall approach.

In a waterfall approach, one stage of development is typically completed before the next stage begins in earnest.

When time isn’t a major factor, this approach works very well, but during the CoVent-19 Challenge, this just wasn’t an option.

Instead, the team used a parallel development approach, meaning that different phases of the project progressed simultaneously.

On the communication side, video conferencing allowed the team to bring in other talented professionals who might not have been able to participate otherwise.

Sinha summarized these unique changes to the design process and admitted that there is potential for them to be used again in the future, in more typical circumstances.

“The pneumatics, mechanics, user interface, and electronics of the ventilator were all being studied and tested simultaneously while it was being designed and researched. Because of the lockdown we were also able to collaborate seamlessly with highly skilled people regardless of their location. I think both of these approaches can be used in the future.”

Atypical circumstances can force professionals to discover and prototype alternate methods, and while these alternate methods may not be appropriate for every conceivable situation, having these methods available give professionals more options.

The more options, the more tools available at any given time, the better the chances of being able to use an optimal method for each situation.

Looking back

We asked Sinha to look back on her experiences during the CoVent-19 Challenge and comment on whether there is any aspect of the project that she would approach in a different way if she had the opportunity to start all over again.

Ultimately, there was one aspect of the process that she would do differently, at least if it was at all possible.

“The only other thing I would add to it is doing more field research. We weren’t really allowed to be in hospitals around COVID patients, for obvious reasons. So I don’t even know if we would have been able to do that, but if there was a possibility, I think we could have learned a lot by going to hospitals and seeing what was happening firsthand.”

This in-person research would have indeed given a much clearer idea of hospital and care conditions as they related to COVID patients, but, as Sinha mentioned above, this type of research would have been both impractical and potentially dangerous.

Still, this offers a lesson for other professional designers, especially those who design medical equipment or anything else that needs to be functional and effective more than anything else.

If possible, learn as much as you can about the conditions where your product will be used and the people who will most likely be using the product.

How would the product fare over time in demanding conditions? Which features or design choices have the highest chance of causing unintended problems for the user?

Going into the early stages of the design process with as much information as possible is only going to help you make what might otherwise be difficult design decisions.

Aftereffects

As another example of how the CoVent-19 Challenge wasn’t just an isolated event, Sinha made it clear that the project had a lasting impact on her professional goals and the kind of work she hopes to contribute toward in the near future.

“I think my interest in user experience and strategy has grown, and I have always wanted to be part of medical and social impact projects. My new role at Fjord will hopefully bring more opportunities for socially impactful projects.”

So while this project didn’t lead to Sinha working solely on medical devices, it did offer a glimpse into projects that can affect real-world change in a positive way.

This is why it’s important to present design as something much larger than the application of aesthetics.

Designers can choose to pursue projects and concepts that could have wide-ranging effects on how people live their lives.

Many talented and sought-after designers, like Sinha, are already doing just that.

Indeed, many of the devices and digital experiences we engage with every day were borne from ambitious design ideas and executed by skilled designers and engineers.

This philosophy and source of motivation can even be applied to existing physical and digital products and experiences.

There is always a better idea out there, a better way of doing things. It may take years to arrive at these solutions, but innovation that offers immediate benefits to real people will always be rewarded.